Exil in Paradise. 6 women in 1940s Los Angeles

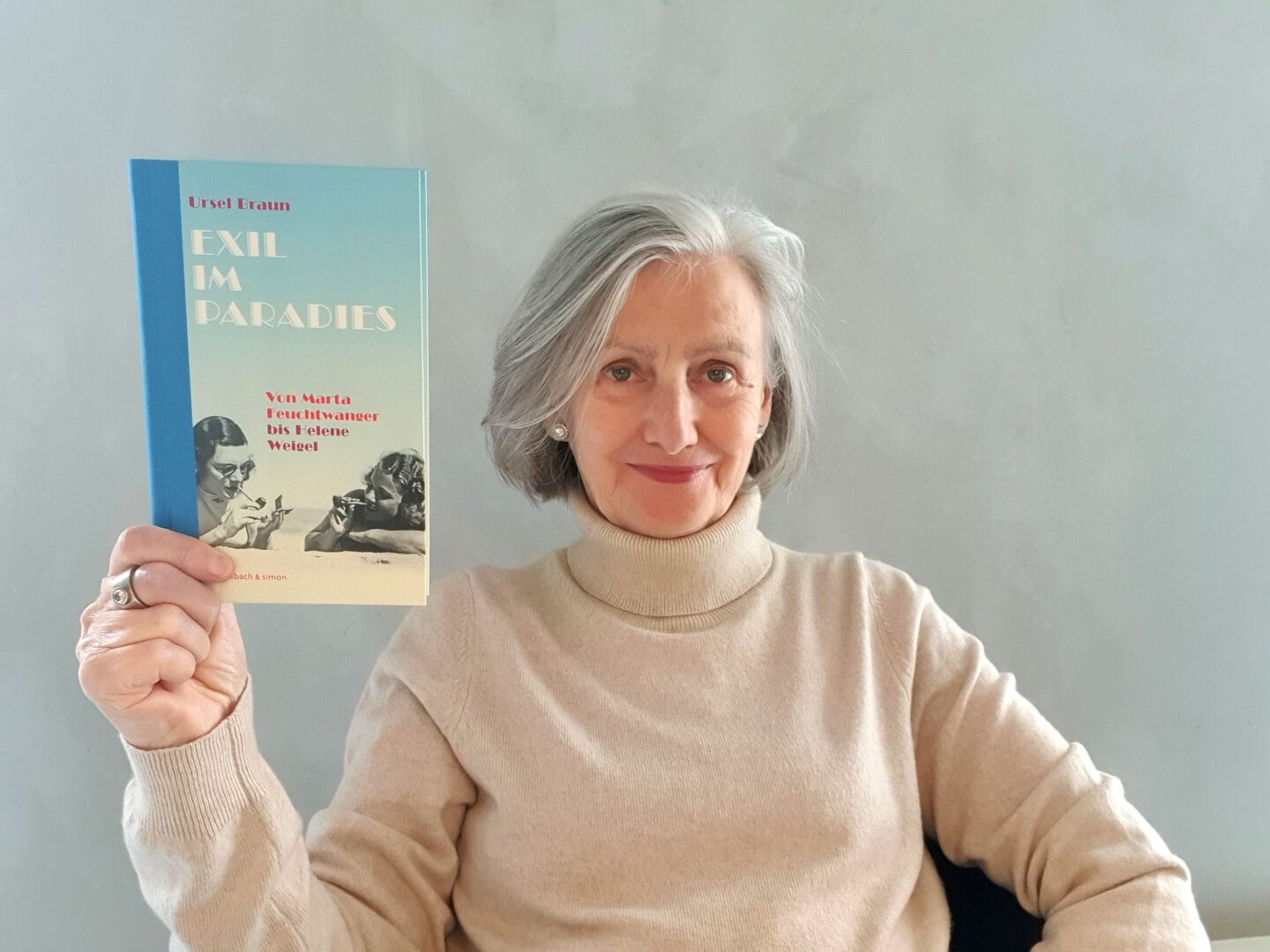

By Ursel Braun

Contents

1940 – Page 7

In Salka’s salon, guests take aim at Hitler´s portrait with darts – Katia enjoys a genteel summer retreat with Thomas and poodle Niko in Pacific Palisades – Nelly struggles with the tricky “th,” the guttural “r,” and the tempations of alcohol – A diva steps onto the stage.

1941 – Page 39

Marta goes skiing in Yosemite – Salka serves her “tarte de résistance” for Heinrich Mann’s 70th birthday – Marta rebuffs Henry Miller – Helene arrives in Los Angeles with the Brecht entourage – Alma enjoys being eccentric – Katia receives sad news – Helene on the beach – Alma expects great things from Werfel – Nelly pawns her jewelry – Salka moves heaven and earth to get her mother out of Europe – The German exiles become “enemy aliens”

1942 – Page 70

Alma provokes her Jewish guests – Katia moves into “Seven Palms” in Pacific Palisades – Wanted: a film role for Helene – Dinner at Alma’s in the Hollywood Hills – Nelly suffers a serious breakdown – Alma buys a Steinway grand piano – Helene, Salka, and Marta form a network – Alma meets Erich Maria Remarque – For Salka, one blow follows another

1943 – Page 93

Marta transforms a dilapidated house into a luxurious oasis – Helene and Marta mock the FBI – Evening gathering at Salka’s – Alma now lives under a roof of fear – Scenes from a marriage at the Feuchtwanger house – Salka suffers from fatigue

1944 – Page 109

Nelly survives a suicide attempt – Berlin’s most famous actress gets only a silent 30-second role in Hollywood – Exile has broken a person, and the mourners gather – Helene considers jealousy unnecessary – Salka is forced to take in paying guests

1945 – Page 119

Marta builds bookshelves – War ends! Corks pop at Salka’s – Helene fears her best years are behind her – There’s no talk of triumph for Katia – Werfel dies, and Alma resumes the role of widow – Salka and Brecht write a screenplay – Under the Christmas tree at Villa “Seven Palms”

Epilogue – Page 133

Literature – Page 138

Acknowledgements – Page 14

1940

In Salka’s salon, guests take aim at Hitler’s portrait with darts -Nelly struggles with the tricky“th,” the guttural “r,” and the temptations of alcohol.

Salka

In 1940, Santa Monica is still a sleepy coastal town, picturesquely perched on the edge of the Pacific, far enough from Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles to preserve its own rhythm — slower, softer, vaguely European. On Mabery Road, above the bay, stands a two-story house with a green roof and window frames painted to match. Timber-framed, with gables and bay windows, it has a reassuring, Old World charm — a home that might just as well belong on the outskirts of Salzburg or Munich.

Here lives Salka Viertel, an actress of considerable grace, alongside her husband, the Viennese writer and director Berthold Viertel, and their three sons.

Every Sunday, Salka opens her doors for what quickly becomes one of the most talked-about salons in Los Angeles — a tradition of cultivated Europeann circles that she introduced into Californian soil, where it takes root and blossoms. These gatherings are unlike anything the city has seen: intellectual, improvisational, electric. A curated guest list ensures an alchemy of cultures: émigré filmmakers, studio executives, free spirits, and for a touch oft he erotic, with some birds of paradise. The result is dazzling.

Since 1933, the number of German-speaking émigrés has swelled. At Salka’s house, they find something that is familiar: long conversations about art and politics, an entertaining and often brilliant exchange fo ideas and convictions, debated until dusk.

Salka, with her soft authority and irrepressible charm, is a hostess of rare quality — warm, but never cloying; cultivated, but never pretentious. She offers her guests not only shelter but a fleeting sense of home. Her prominent guests can relax and enjoy themselves out of the public eye.

Billy Wilder unpacks his chessboard and starts a match with Marlene Dietrich. Arnold Schönberg and Charlie Chaplin challenge each other to a game of ping-pong. Others put records on the gramophone and dance the shimmy or the tango. The ocean is just a stroll away — a brief detour under the Pacific Coast Highway leads to the wide-open beach, where one can cool off before dinner.

In the golden Californian light, beneath a magnolia tree, Salka serves what she knows best: robust Viennese cuisine. Goulash, simmered for hours in cast iron. A hearty vegetable soup with little sausages. For desert there is always one of her delicious home-made cakes — her Gugelhupf, a crisp apple strudel, or, on more ceremonial days, the pièce de résistance: her own recipe for Sachertorte.

The highlight of these Sundays is an amusing competition: a dart game in which the guests take aim at a photo of Adolf Hitler tacked to the wall.

But the apparent ease of this life is deceptive. Behind the laughter and candlelight, there is grief, fear, and helplessness. The Viertels and their circle follow with growing horror the destruction of their homeland.

Salka was born in 1889 as Salomea Sara Steuermann in Sombor, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As the daughter of a Jewish lawyer and mayor, she grew up surrounded by books, music, and servants. Against her parents’ wishes, she pursued the stage, performing across Europe — and most notably in Berlin during the heady, chaotic years of the Weimar Republic.

She understood early the danger that was coming. Long before antisemitism became German state policy, she had seen ist destructive intentions. That made her unusually attuned to the desperation of those still trapped in Europe, desperately trying to find safety and felle tot he United States.

After the Reichstag fire in February 1933, an exodus of writers, artists, intellectuals began who tried to escape from a homeland turned hostile. It was a migration on a scale the world had not seen before. Not a single day passes in which Salka is not asked for help. She can barely summon the courage to open her mail. „Years of the devil“ is the lable her secretary gives tot he file in which she collects the letters and petitions.

Out of gratitude for the safety she herself has found in the United States, Salka takes on the burden with courage — and with heart. Her “Unbelievable Heart” (Mein unbelehrbares Herz), as she later titled her memoir, became legendary. In her house in Santa Monica she offers shelter, introductions, advice, warmth to countless newly arrived émigrés, whose lives and souls are shattered by the Nazis.

The smells from Salka´s kitchen are the same as those in the kitchens of their mothers and grandmothers. The books on her shelves are the same they had to leave behind..

Salka herself had arrived in Los Angeles well before the storm, in 1928, with Berthold and their sons. Money was tight and when Fox Film offered Berthold a lucrative three-year contract — arranged through his friend, the legendary director F.W. Murnau — they packed up their lives in Berlin and came west. It was meant to be a brief detour. A few years in the studios, then back home. That, at least, was the plan.

But Los Angeles, for all its sunshine, was a pale substitute for Berlin. To Salka, Hollywood was a cocktail too sweet, too predictable. The parties were boring: men smoked cigars and struck deals by the bar; women lounged poolside like ornaments, sighing about their maids.

To endure it, Salka, the self-confident, spirited and energetic European does what she has always done — she works. She learns English, takes driving lessons, and picks up small roles in films. But her height of 5 feet 5 makes her too tall for the film industry oft he day. On top she is too curvaceous, and, at forty, far too old..

There are beautiful women everywhere in Hollywood. But one, one day, strikes her as utterly singular. At a party hosted by Ernst Lubitsch, she sees her: tall, statuesque, dressed in a black man’s suit, with sneakers and a flower in her lapel. Standing apart, observing the crowd with those shadowed, expressionless eyes — part melancholy, part menace.

It is Greta Garbo. (…)

While Berthold, the eloquent Viennese coffee house intellectual unwilling to conform grows disillusioned with Hollywood’s simplistic narratives, Salka is able to establish herself in the film studios. She is hired by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to develop screenplays for Garbo — and, remarkably, rises to become one of the most successful female screenwriters in 1930s Hollywood. She co-writes five screenplays for Garbo, including Queen Christina and Anna Karenina — two of the diva’s most enduring films.

Salka´s meteoric career does not make the Viertels´ marriage any easier. The couple soons go their separate ways — gently and respectfully. He shuttles between New York, Europe, and Los Angeles. She remains in Santa Monica, a single working mother — rare enough at the time — raising three boys and supporting not only them but, in her characteristic generosity, also her husband, parents, and in-laws in Europe who live under increasingly difficult conditions.

Truly, Salka does not live conventionally. Nor does she love conventionally. In her early forties, she falls for a man half her age: Gottfried Reinhardt, son of the famed theater director Max Reinhardt.

„I didn´t leap into the affair,“ she wrote. „I glided into it, which many found unhealthy.“

Each summer, Berthold returns for a few weeks’ holiday. The children are overjoyed when their father comes home. They adapt to the unusual arrangement. Father is father, and Gottfried is the exciting “uncle” who takes them on joyrides along the coast in his roadster.

Periodically, Salka and Gottfried live and work together — until, ten years later, one of them will break the other’s heart.

Nelly

On October 13, 1940, around 9 a.m., the SS Nea Hellas approaches New York. On board the overcrowded ship are refugees from Europe. They gather on deck and wait for the Statue of Liberty to emerge from the drifting morning mist. In Hoboken harbour, a small boat carrying reporters comes alongside the ocean liner. They are familiar with the passenger lists and know that sixteen prominent German language writers and their wives are among the émigrés. Among them Franz Werfel and his wife Alma Mahler Werfel, as well as Golo, Heinrich, and Nelly Mann.

Luckily, they had gotten cabins. Some passengers had to sleep in the corridors, on the floor of the library, or on the billiard tables. Others were quartered in the belly of the ship, on hard mattresses in stacked metal bunks, and plagued by bedbugs. The nine day crossing seemed endless to everyone. As the ship rolled and pitched on the autumnally choppy Atlantic, Heinrich Mann became so seasick that he could not leave his bed. Nelly paced about and saw fear tormented people lying out in the open near the lifeboats, tormented by the fear of a torpedo attack from German submarines.

But now, at long last, New York has been reached. On the landing pier, Thomas and Katia Mann are already waiting. Despite the relief that his brother has succeeded in fleeing Europe, Thomas Mann is driven by a worry. Regrettably, “that Mrs.” is also on board. Thomas Mann would never be able to utter the name of Heinrich’s wife for the rest of his life. Too foreign are, to the pedantic Nobel laureate for literature who cultivates his bourgeois allure Nelly’s demonstrative femininity, her casually irreverent Berlin idiom, and her lack of education.

That his brother has been living with Nelly Kröger Mann for years to the dismay of the family, that she has voluntarily followed Heinrich into exile to southern France and thereby abandoned her security in Germany — none of this counts for Thomas or for Katia. Nelly is the socially improper taint on the family. It is part of the tragedy of Nelly Kröger Mann’s life that the members of the émigré bohemia mock her behind her back.

By René Schickele, for instance, whose ironic remark about Nelly becomes legendary. “In grand summer dress Mrs. Kröger. She is floating airily and intensely toward us.“

Also Lion Feuchtwanger’s label for her – “Mrs. Professor Filth”(an allusion tot he lead character in Heinrich Mann´s novel „The Blue Angel“) – spreads quickly. Indeed Heinrich Mann and Nelly Kröger Mann are an uneven pair. He, the older writer from a Lübeck senatorial family, a distinguished figure with impeccable manners; she his second wife, 27 years younger, tall and blonde, who gives him warmth, naturalness, joie de vivre, and sexual fulfillment. Illegitimate daughter of a maid in a village in the Baltic hinterland, she had seized one of the few opportunities open to women without education in 1920s Berlin. She earned her living as a hostess (Animierdame) in the “Bar Bajadere” on Kleiststraße. There the successful writer Heinrich Mann also frequented, and between them a love story was kindled that seems like a fairy tale.

An exhausting escape across Europe lies behind the two, at their arrival in New York. But Heinrich and Nelly Mann cannot stay here long; they begin a long railroad journey across a continent unfamiliar to them. Their destination is Los Angeles. Heinrich must take up his position as a screenwriter in Hollywood. Warner Brothers Pictures has, through the European Film Fund (EFF), given him a one year contract — the basis for their admission to the United States. At least now they are traveling on the comfortable Pullman train toward the West Coast. A streamlined locomotive draws 14 cars fitted with lounges, reading chairs, and sleeping compartments. The journey takes, with a transfer in Chicago, 54 hours. In the evenings their compartment is converted into a sleeping car by a porter, and in the morning reverted to its original state. Waiters serve three meals per day in the dining car, which reinforces the bon vivant Heinrich Mann in his prejudice that in America there is nothing but “cheap restaurants.” The cutlet is as big as a tennis racket and buried under a red ketchup sauce. The salad consists of the hard leaves of a plant called iceberg, served with a pale-orange sauce whose name “French dressing” seems to Heinrich Mann an insult to the French cuisine which he cherishes. Worst of all is the coffee — so thin that the bottom of the cup remains visible. In plain words: “flower petal coffee.”

Nelly gazes from the train window at the alien beauty of mesas and lush sagebrush. She dreams of their future life in California. In the “City of Angels” she and Heinrich will finally enjoy life again. They will live in their own house with a fireplace and a garden always in bloom. She will have dogs and canaries, perhaps even a peacock.

As the sun rises the next morning, the train rolls through orange groves. They have made it! They are in California. At Union Station in Los Angeles, Nelly is dazzled by the blinding glare of the autumn sun. An old friend, the émigré writer Bruno Frank,awaits them there. He has lived in the United States since 1937. On the drive to their hotel, they ride in his gleaming automobile over straight roads with no sidewalks and see a strange world: drugstores, billiard halls, import and export shops, liquor stores, and a pink cheap hotel. On street corners telephone poles hold tattered notices. One roof looks like a mushroom, one restaurant is shaped like a hat. In the opposite lane gigantic trucks rumble past. In the distance lie oil derricks and a shining blue strip— the Pacific Ocean. The thought of being almost 9,000 kilometers away from the knobby, ancient pines and the tidal channels of the Baltic almost breaks Nelly`s heart.

After the first days in a hotel they move into a small furnished apartment, conveniently located between the Hollywood studios and the houses of well off émigrés in the hills between Beverly Hills and Santa Monica. They all know each other from Munich, Berlin, Paris, or Sanary sur Mer and hope to be able to invite the much esteemed newcomer soon. If only there wasn´t his problematic wife! (…)

In Los Angeles, from the start, Nelly wants to do everything right. She organizes domestic affairs so her husband can work. He grants her full authority over his bank account; this is more convenient for him. She teaches herself the new language — more badly than well. “My name is Nelly. This is my husband. He is a writer.” The difficulty of pronouncing the complicated “th” and the guttural “r” seems insurmountable. She gets a driver’s license and buys a car so that she can drive Heinrich to the studio each morning and pick him up late in the afternoon. She takes him to the doctor, the hair dresser, the newsstand. She has business cards and stationery printed: Nell Kroeger Mann, 264 South Doheny Drive, Beverly Hills. She washes and irons his snow-white shirts, the light summer suit, and his pocket squares. She deals with the naturalization paperwork. She writes letters to friends and relatives in Europe to stay in touch. She invites his famous friends to dinner. After all, she can cook! Three courses: a fine bouillabaisse, lobster with tarragon, and for dessert a Lübeck style red berry compote. But before the guests arrive her personal demons catch up with her. Is it her fear of intellectual conversation — or has she fallen asleep? In any case, she does not join the meal. The guests are most polite; they give no sign. But later they speculate that, once again, the hostess may have drunk too much of the cooking wine. Indeed Nelly’s handling of alcohol becomes more menacing, and with that her social isolation grows. In the elite émigré circle she can not hope for sympathy— especially if she has been drinking. (…)

Alma

Alma Mahler-Werfel — née Schindler, widowedby Gustav Mahler, divorced from Walter Gropius asks her chauffeur – just days after arriving in Los Angeles – to drive her to a party hostet by Max Reinhardt. The guests observe: The visitor, who in her youth in the salons imperial Vienna was a notorious femme fatale is no longer a beauty in the conventional sense. Like an actress taking the stage, she enters he room, carrying herself with conviction and theatrical certainty of her own allure. Her black flowing evening gown, the long strand of pearls and a regal ermine cape, lend her the aura of the grande dame she once was. She pauses dramatically for a moment, sees the host, furries over to him with outstretched arms and introduces herself.

“I am Alma Mahler.”

That her current husband, Franz Werfel, is standing quietly next to herin this very moment seems to escape her attention entirely.

The label „diva“ fits Alma Mahler-Werfel so well, it seemed to habe been created with her in mind. Even as an émigrée, she remains imperiously self-possessed, pushing aside both inner and outer conflicts with practiced ease. Nearly thirty years after the death of her first husband — the composer and Viennese court opera director Gustav Mahler — and two additional marriages later, she remains Mahler´s full-time widow. „La grand veuve“, the frande widow, as Thomas Mann calls her. That she thereby insults her currant husband, is just part of her strategy. It includes attracting men, captivating them, and in the end cruelly tormenting them. (…)

1941

Helene arrives in Los Angeles with the Brecht entourage – The German émigrés become „hostile foreigners“. Helene on the beach (…)

Helene

On July 21, 1941, the great actress Helene Weigel arrives exhausted in the port of Los Angeles. One of the few to escape at the very last moment, she has managed to board the Swedish ship SS Annie Johnson and leave the Soviet Union just before Germany invaded the country.

Ever since she had to secretly escape Berlin after Hitler’s rise to power, the Jewish actress had been on the run — with her husband, Bertolt Brecht, and their two children: sixteen-year-old Stefan and ten-year-old Barbara. Also with them is Ruth Berlau, Brecht’s current lover.

Marta Feuchtwanger, together with her husband´s secretary, has come to the pier to pick up her old friends, ready with two cars to bring the group into the city. It is a hot summer day, and before anything else Brecht would like some ice cream.

In truth, things might go well for Helene from now on. Marta has done everything she can to ease their arrival: she has rented a small house fort he Brecht entourage in Santa Monica, at 1954 Argyle Avenue, and ensured that Ruth Berlau will temporarily stay with friends — with the unspoken hope, at least from Helene’s perspective, that she will soon continue her journey to the East Coast.

But Brecht arrives in the US with a negative attitude, full of suspicion and prejudice. The soft hills of Los Angeles look to him like stage decor. He can´t breathe in the furnished Spanish-style house with its pink-painted doors and complains that there is no separate entrance to his study — no discreet path for female visitors.

Helene, the calm and competent center of the Brecht family, quietly smiles to herself and lights a cigarette. Within a month, she finds another house — this time at 817 25th Street — but it, too, fails to please him. He hasn’t chosen this place, nor the journey that has brought him here. He has been forced into exile for eight long years, and he is thoroughly fed up. He bitterly calls the new house a “terrible little bourgeois villa with a tiny garden”, surrounded by “tacky little bourgeois houses with their depressing prettiness.”

Practical and pragmatic as ever, Helene turns to the Salvation Army for furniture. She is determined to give Brecht the stability to work — to once again contribute to the family’s survival. Normality must finally rule the day not less that their daughter Barbara can recover from her tuberculosis. The child will spend the next six months in bed before she can attend school. Helene builds her a dollhouse out of boxes and brown paper. She buys fabric, sews nightshirts and collarless grey jackets for the family, fills out forms, and applies for welfare: $120 a month, of which $50 go to rent. There is little left to live on four a family of four. Wealthier émigrés, like the Feuchtwangers or director Fritz Lang, help cover the rest. (…)

Helene dares to hope again. Perhaps, in this new world, the painful love triangle will become more bearable. Perhaps she can finally act again. Hollywood is always looking for new faces.

Who knows? Maybe a great film role is just around the corner.

Katia, Salka, Nelly, Helene, and Alma

On the morning of 7 December, 1941, Katia Mann finds her Tommy distressed in the bedroom wearing his dark-red dressing-gown. While he is drinking his morning coffee from a little mocha cup, he hears the news coming from the small radio next to his bed: the Japanese have bombed the naval base at Pearl Harbor on one of the Hawaiian islands. As a consequence, the United States gives up its neutrality and enters the war. Finally!

All members of the German exile community have been waiting for this news for a long time. Hope arises that this could be the turning point of the war, and that Hitler might soon be defeated. But a dramatic consequence of America entering the war is that the Japanese, German, and Italian residents are immediately considered tob e hostile foreigners. All Germans, whether Jewish or not, must register with the authorities and report to them once a month. They are subject to a nighttime curfew between 8:00pm and 6:00am. They are not permitted to travel more than five miles from their place of residence, may no longer listen to shortwave radio, and their bank accounts are frozen. Police warn that speaking German in public could be dangerous. In California, because of its geographical location and a concentration of weapons factories, panic is spreading. Immediately rumorsbegin to circulate that the Japanese are planning an invasion and enemy submarines are already approaching the coast. […]

Katia Mann, as a woman good with numbers, immediateliy realizes: from now on their remaining money must last Tommy and her, their six children – who, unfortunately, are still not able to support themselves – and Heinrich and “the wife.” On a walk through the lemon groves, the Manns audibly speak German with one another. Suddenly a policeman turns up in front of them, growling and snarling forebodingly, before bursting out: “Stop that damned Nazi-talk! Speak English!”

Even in a situation like this, Salka Viertel immediately thinks of others first. Her Mr. Yoshida is one of the hundreds of Japanese gardeners in Los Angeles. Three times a week, he comes to her house to mow and water the lawn. With his rattling Jeep he drives from house to house from early morning until late in the evening. His wife cleans and does laundry for the Schönbergs and the Reinhardts. His daughter, Peggy, serves at Salka’s dinner parties. They all consider themselves American, and now they are being forced to sell everything they own and move to an internment camp in the desert outside Los Angeles. Wooden barracks were hastily erected there for 120,000 Japanese-Americans. Six months after their relocation, Peggy sends photos from the camp. With skill and hard work, the Japanese have transformed it into a blooming garden. What they miss there though is fruit. Right away, Salka sends crates of oranges and grapefruits.

Nelly Kröger-Mann is afraid. All Americans have been asked to report suspicious individuals tot he authorities. Anyone can be a spy. The waiter, the gardener, the neighbor. The people living on their street stare at her. Every noise gives her a start. She listens for footsteps constantly. And then the telephone rings and a voice says: “Go back to where you came from!” The nights are long now, and they are lonely. What shall become of them, if the war never ends and they are never at home anywhere again?

Again and again, FBI agents show up at Helene Weigel’s front door. Suspicious neighbors saw Barbara, her eleven-year-old daughter, having lunch in a diner frequented by workers from the nearby Douglas aircraft factory. They reported the girl. Now she is suspected of spying on the American war industry.

Alma Mahler-Werfel expects the worst. Under no circumstances does she want to fall into the hands of the Japanese and considers moving inland to Denver or Colorado Springs. She makes unmistakably clear to Werfel that, with America’s entry into the war, nationalism will flourish even more in this desolate country to which he has dragged her. She tells him that he will have a hard time staying on top and will have to work even harder. […]

Helene

Exile effects some harder than others. For Helene, it robs her of her language, her audience, and her profession. It is not easy for her to distinguish among all the famous actresses in Hollywood. They all look the same, say the same polite lines, wear the same tailored dresses and the same hair styles.

In the dream factory perfection rules. Each pencil-lined eye, every curl, every low-cut dress, is fixed so flawlessly and firmly in its intended place that Helene wonders at how is even possible. Presumably, with a will of having one´s teeth fixed, subject oneself to a permanent diet, and wear curled hairstyles sprayed stiff with tons of hairspray.

“Small figure – big fighter,” that’s how Brecht describes the „Helletier,“ as he calls his wife.

Her acting is never pleasing but truthful and intense. She has no understanding whatsoever for the false glamour of the film studios. But she is ambitious, and studies English with determination. She even carries around her grammar book under her arm when walking along the Pacific. Every day she does her speech and body exercises to maintain her great acting talent.

She goes to auditions without makeup, her hair stringy, combed back strictly and tied into a knot at the nape of her neck; wearing a collarless grey jacket, loose, unpressed trousers, and flat shoes. She tells Brecht:

„I’m not dressing up—I go as THE Weigel.“

From under the studio lights, she looks at the director, brimming with talent and energy, one eyebrow raised, a burning slim cigarette between her fingers. Her English is strongly colored by German.

A strong and unconventional personality, radiating pride and nonchalance, with a hollowed-out face, dark circles under her eyes, and a gaze that’s anything but friendly.

So much avant-garde demands too much for Hollywood.

1942

Katia moves into “Seven Palms” in Pacific Palisades – Wanted: a film role for Helene – Dinner at Alma’s in the Hollywood Hills – Nelly suffers a serious breakdown […]

Katia

Nothing works in the life of the great writer without “Mrs. Thomas Mann” – as her letterhead reads. Even more so in emigration. She is an impressive, self-confident woman who always takes care of everything, never seems overburdened, never complains, and always maintains composure. At least, on the outside. She is the center of the Mann household and truly irreplacable. Especially not for Thomas. In his eyes, she is “the great matter of my life;” in her own sober and self-deprecating words “my insignificant self”. In the summer of 1941, Katia Mann turns 57. The dazzling, capricious “oriental princess” with the delicate figure, catlike eyes, and jet-black hair once cascading over her shoulders has become a robust woman with a masculine haircut – one who, over the years, has come to resemble her husband more and more.

The emigration story of Katia and Thomas Mann’s differs in many ways from the miserable odysseys of most other émigrés fleeing the Nazi-regime. Immediately after Hitler’s rise to power, the literary Nobel laureate and his wife move to Switzerland with their youngest children, Elisabeth and Michael. But as German troops annexed neighboring Austria, Katia recognized that it was no longer safe in Europe. They had to leave the continent.

In 1938, the Manns travelled first-class on a luxury liner to the US, where they were welcomed with open arms. Thomas Mann’s American publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, promoted him as the Greatest Living Man of Letters. Since 1937, Mann has an honorary doctorate from Harvard University and has an excellent American network that extends all the way to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. (…)

After eight months of construction, on February 5, 1942, Thomas and Katia Mann finally move into their new home.The man of the house knows that this building project was a major effort for his wife, one that pushed even her to her limits. He wished it to reflect his prominent position among the exiles in California.

Like an elegant ship, the elongated, white house towers on a hill in Pacific Palisades, overlooking the Santa Monica Bay. Attached to the simple, two-story flat-roofed building is a square structure offset from the main axis and separated from the rest of the house by a three-meter wall. This is Thomas Mann’s private area.On the ground floor of his studio is his study.

A small spiral staircase leads up to the bedroom, complete with a large bathroom and a rooftop terrace. A private hallway lined with floor-to-ceiling bookcases leads directly into the salon oft he house. When the door is closed, the writer can work in total isolation from the rest of the household.

On move-in day, thanks to Katia’s flawless organization, Thomas Mann finds his study set up just as he is used to whenever he arrives at a new phase of his life. The small sofa is already sitting in front of the bookcase on one end of which he sits and writes his texts, using a small lectern and his fountain pen. Precisely in his field of view, across from his desk, hangs “The Little Lenbach,” a portrait of the young Katia. The entire Pringsheim family had, at the request of her father, been painted by Munich’s court painter Franz von Lenbach. The portrait shows the eight-year-old in a dark green dress with fur trim, her deep black eyes in a pale face, and a red cap upon her black hair.

Each and every object on his desk, the medals, the ivory tooth used as a letter opener, the Egyptian servant, stands in its proper place, just as before in Munich, Küsnacht, and Princeton. A guarantee of the absolutely necessary uniformity of his everyday life.

But one thing sets this office apart from all previous ones: From his armchair behind the desk, Thomas Mann now looks into a room brightly lit by the Californian sun and, through a window as wide as the room itself, out to the Pacific Ocean and Santa Monica bay.

In case the sunlight should become too harsh for his closed eyes while he rests on the sofa, Katia has installed Venetian blinds. The day after moving in, the writer can note in his diary with satisfaction: „Spent the first night in the new bedroom under my own silk sheet very well.“ (…)

In California as before, Katia meets her Tommy each morning at 8:30am for their breakfast. She knows that the meticulous regularity of his daily routine is the foundation of his success, and organizes his life accordingly. He is already dressed in his light, white summer suit with the double-breasted jacket and white shoes. At exactly 9:00am, he shuts the door behind himself and begins working. At 11:15am, she brings him his small morning cocktail: one beaten egg yolk, two teaspoons of sugar, topped off with Cinzano.

After exactly three hours, he puts his pen down. He combs his hair, straightens the bow tie, puts on his Panama hat, and hooks the handle of his walking cane over his left arm. A final look in the mirror and then he heads off on his walk. At 1:30pm sharp, it’s lunchtime . Afterwards, he smokes a cigar on the terrace and begins his extensive reading of American newspapers and magazines like The New York Times and The Nation. At 4:00pm, tea is served, followed by phone calls, further reading, and corrections. At 7:00pm, on the dot: dinner.

Katia Mann is in charge of their evening program that includes concerts at the legendary Hollywood Bowl, movies, and get-togethers with longtime friends from Munich, like the writer Bruno Frank and the conductor Bruno Walter, who, like the Manns, have chosen California as their place of exile and live about four miles away in Beverly Hills. By American standards, so close they are practically neighbors.

Ever since the exodus from Europe began in 1933, Los Angeles became the insider tip among émigrés. A good 10,000 refugees have come from Germany and Austria to the American west coast. In the north, in Berkeley and San Francisco, many scientists teach at the universities. In the Southern neighbourhoods of Los Angeles, Pacific Palisades, Brentwood, Santa Monica, and Beverly Hills, live writers, composers, conductors, and actors some of whom the Manns have known from Munich. So much intellect and talent come together in this one place at the beginning of the 1940s that Ludwig Marcuse remarks in his recollections: “I hardly thought about the fact that there were also Americans here. I felt like I was sitting in the middle of the Weimar Republic.” Accordingly, the colony soon came tob e known as “New Weimar.” Just as in the Weimar of Goethe’s time, here too intellectuals, scientists, and artists live in close proximity. […]

Helene

Brecht is fuming mad once again. He writes: “Los Angeles is a Tahiti in the form of a metropolis; rightnow I am looking out at a little garden with lawn, red blooming bushes, a palm tree, and white garden chairs. (…) They have nature here only because everything is so artificial; they even have a heightened sense of nature. It seems out of place. (…) But you learn that all this green is wrested from the desert only through irrigation systems. Scratch a little, and the desert comes through. Don’t pay the water bill and nothing blooms anymore.”

Despite his efforts, he hardly succeeds in placing his work. The screenplay for the film Hangmen also die! – to be released the following year – that tells the story of the assassination of Reichsprotektor, Reinhard Heydrich, in occupied Prague remains an exception. The director is Fritz Lang, an émigré like Brecht and Weigel. They consider him a friend.

Brecht pleads with Lang to give his wife a small role in the film. Both men agree in writing that Weigel shall play the old vegetable seller Dvorak, who is interrogated. She has almost no lines because Weigel’s German accent sounds unpleasant to American ears. Brecht, therefore, created a silent part for his wife, but one of Lang´s assistants adds a few lines for her to the script. Lang insists that the character speaks without accent. He conducts a short sound test with Weigel, promises further tests, but leaves her waiting, only to remove her from the cast list without informing her. Helene is outraged and Brecht demonstrates his solidarity with her. He walks out of Fritz Lang’s studio and cuts off all contact with him.

Helene analyzes her situation with brutal honesty. Her previously pragmatic attitude gives way more and more to despair. Her career as an actress is at a standstill in American exile, as she relies on the German language and the German theatrical tradition. What remains for her now: She hast o manage her family’s daily life, endure her husband’s erotic escapades, maintain the façade of a happy family in front of her children, and withstand the fear she has for the fate of her father in Vienna.

At this point, she does not yet know that he has already been deported to the ghetto in Łódź, then called Litzmannstadt, and died there.

Alma

Madame Mahler-Werfel sent out invitations for one of her legendary dinner parties – to Thomas and Katia Mann, the composer Erich Korngold, the Arlts, Heinrich and Nelly Mann, and Golo Mann. She writes in huge gothic letters on handmade paper; only three lines fit on a single page. At the festive dinner on 1 April, she proves once again her talents as a hostess. Smiling lavishly at the illustrious circle, she has an opulent meal served together with Californian Burgundy and Champagne. None of her guests questions her social and artistic supremacy.

That night, she notes into her diary, arrogant and biting as always, that the “fool,” Heinrich Mann, made a disastrous impression, especially “the slackening and falling agape of his lower jaw.” It is “an omen of death.”

And as for what could possibly attach him to “that washerwoman” would forever remain a mystery to her.

Nelly

Nelly Kröger-Mann does her best but their finances still fall short. The couple must move once again, this time to 301 South Swall Drive. It is a shabby apartment with bare walls, so dark that they leave the lights on all day. Heinrich hardly seems to notice; he lives in his own world and still has his pretensions. “Where does one dine here?” he asks as they are moving in, for he still speaks like the son of a Patrician from Lübeck. Nelly pawns the furniture, not yet paid in full, in order to pay off the outstanding balance on the rent. Five dollars for the desk that she bought one year ago for fifty, three dollars for the desk chair and two dollars for the rug.

The only thing that will help now is a real crash. Alcohol – as she has known for a while – puts her into afloating, happy state free from everyday burdens, financial worries, and the pressure to meet expectations. But the buzz does not go well for long. She is arrested by police for driving while drunk and must spend a dreadfully long night in jail. The next morning, she is released on 250 dollar bail which Heinrich quickly from his friends. On 9 March, 1942, the court orders Nelly Kröger-Mann to 60 days in jail, suspended for two years of probation.

As if her pressures were not great enough, she is also worrying about Heinrich’s health. His doctor speaks of a nervous heart condition and arteriosclerosis. To top it all off, he has dental problems and needs dentures. The cost: 235 dollars. Just how are they supposed to go on? Nelly finds a poorly paid job ironing at a laundry service. When Heinrich has guests, and discusses a speech or a newspaper article with them, no one is supposed to notice how desperate things really are. She cooks a French onion soup and fish steamed on lemon slices. In the days following, they get by eating rice and oatmeal, rice and beans, rice and lentils. Secretly, she buys alcohol at the supermarket – the hard stuff: whisky, rum, cognac. Their circumstances are far too depressing.

In the house of Thomas Mann, Nelly alone is blamed for the financial misery.

The concern for Heinrich is so great that they once again they consider how this problem might be solved. Erika Mann and Heinrich Mann’s physician conspire in an attempt to ship off “the drunken lush” – as Katia Mann calls Nelly in letters to her children – to the east coast. Heinrich Mann unaware of the plan, will be temporarily given accommodation at his brother’s, where he shall be convinced to finally end his marriage to this “pernicious piece” – Katia’s name for Nelly.

Despite all the expressions of love from her husband, who makes it very clear to his brother that he will not give her up, Nelly’s conspicuous behavioral problems increase. On 26 June, 1942, Heinrich and by necessity as his chauffeur, Nelly, are invited to Thomas and Katia Mann’s house, along with the actor Ludwig Hardt and his wife Julia, Lisl and Bruno Frank, Wilhelm and Charlotte Dieterle, the Feuchtwangers, and the Werfels.

It is supposed to be a grand evening for Heinrich Mann. But at the end of the day, Thomas Mann angrily notes: “The woman was drunk. Loud and impudent. Disrupted Heinrich’s reading from his scenic account of the life of Frederick II. Made me sick. That was the last time she’ll be here. I withdrew without saying goodbye.”

But not without first publicly reprimanding her with an enraged “Quiet back there!” Seldom has Thomas Mann so badly lost his temper. The Exile-bohemia savors the spectacle. […]

1943

Evening party at Salka`s – Scenes of a marriage at the Feuchtwangers´ (…)

Salka

In the summer of 1943, Salka Viertel invites the leading figures of the exile bohemia to an evening gathering. With beer and canapés, the guests including Thomas and Katia Mann, Heinrich and Nelly Mann, the Feuchtwangers, Werfels, Marcuses, Franks, as well as the composer Hanns Eisler discuss the latest reports from Germany. Helene Weigel and Bertolt Brecht are at the party as well.

Between 24 July and 3 August, 1943, British and American air forces attacked Hamburg. In the densely populated city, a devastating firestorm erupted, exacerbated by high temperatures. Hamburg burns for nine days. 40,000 people die in the inferno. Vast sections of the city, including most industrial firms, the harbor, hospitals, schools, and churches are destroyed.

The mood in Pacific Palisades sways back and forth from relief at the imminent end to the war to the grief and bewilderment regarding the human suffering in their homeland. Everyone is shocked by the obliteration of Hamburg, the destruction of churches and hospitals, schools, working-class apartment buildings, and libraries, shocked by the mass panic and the suffering of innocent children. Salka Viertel also brings up the pilots who dropped the bombs. So many were shot down or died in the firestorm. So many of them are young Polish pilots who, in the face of Hitler’s invasion, have led to England and joined the British army.

It becomes a long night.

For nearly all of those gathered, the eleventh year of their exile has begun. A sorrowful anniversary but all have the hope that the Nazi-terror will come to an end in the not too distant future. But how is Germany supposed to continue, a nation that will soon be, in every respect, demoralized and in total collapse? A country in which the people have mutated into blind followers?

Marta

Marta Feuchtwanger likes America – and the Americans like her. She nurtures relationships with her Southern California neighbors. She likes their cheerful nature, even if it seems somewhat naive in her eyes. As Lion writes out a check in a store for a suit, the salesman reads the name Feuchtwanger and cheerfully says: “Good to have you here, folks.” As they are leaving, the man slaps the world-renowned writer on the shoulder and declares that it’s a great honor for his store to have such a well-known man shopping there. “Goodbye, folks!” he calls out behind them. This amuses the Feuchtwangers; they cast off the social-corset of their privileged upbringing long ago and integrated themselves effortlessly into the social fabric of the city. As well-to-do intellectuals, they have an interesting profile. Important figures of the film world like to adorn themselves at parties with the successful writer and his extravagant wife. Of course it is a sensation whenever Marta performs her gymnastic acrobatics around the pool or dives head first into the water. All admire her exotic beauty and her unusual wardrobe. Even Alma Mahler herself says that, from now on, she too will wear only white like Marta. […]

Even though the Feuchtwangers are friendly with many people in Los Angeles, their privacy is sacred to them. Marta runs a tight ship. Guests may only come to the house starting at teatime. There isn’t even a telephone at their home, the Villa Aurora. Anyone who wants to reach the writer or his wife by phone, must call the fish restaurant down below at the beach. Lion is more focused on his work than ever before. The outbreak of the Second World War changed him. From 1943 until his death in 1958, he will write six novels and countless other texts from his office at the Villa Aurora. His most important writer-friend is Bertolt Brecht. The gregarious Brecht found a house in the vicinity and complains: “How can you both live so secluded?” For Brecht, Pacific Palisades doesn’t actually exist. There is nothing there except hills and trees; there’s not even a gas station, a physician, or a pharmacy. “You two could die because there is no help nearby,” he worries. […]

Marta regularly asks over the circle of émigrés. The hostess likes to serve traditional dishes like herring salad with red beets. She bakes her own pretzels and prepares red fruit compote, Salzburger dumplings, and apple strudel from scratch. This anti-homesickness cuisine is like a fortress in a world slipping away. All those in “New Weimar” are wounded, highly intellectual, and plagued by a longing for their lost homeland. The disparity between the sunny carefree life on the Pacific and the hell of war at home, is more and more difficult to endure. “No one was really happy,” Marta Feuchtwanger will later say. “We knew what was happening in Europe.” […)

Lion regards his wife as his most important collaborator and sharpest critic. “He always said: without you, I would not have been able to write the book. But that was of course an exaggeration, ” Marta later said. As a young writer, Lion had been a playwright and had not considered writing novels, because, among other reasons, he could write plays in a short time and writing novels would have demanded considerably more effort. Not until repeated encouragement from Marta, did the world-class novelist to-be complete his first novel. Since the very beginning she has always taken a lively interest in his writing but she also gives him advice about the development of his characters. Inexorably, she corrects all his proofs – a job that he believes only she can do. He knows that her sharp mind, her sound judgement, and her feeling for language are indispensable for his work. In order to optimize his time for writing, she reads the daily newspapers for him, as well as Time and Newsweek, and passes along the articles that are useful to him. Every morning, he reads aloud to her what he wrote the day before. Then they discuss it. Frequently, she also negotiates the contracts with agents and publishers.

And the many affairs? Marta puts it in a nutshell: A woman who is married to a genius, must turn a blind eye to some things. For the most part, she is polite to the women who Lion takes to bed. Only they should never attempt to challenge her place as his spouse. Then she becomes unpleasant. Then she will begin Strindberg-ing, as Lion calls it. She would often have cause to be jealous but, according to her own account, she simply is not. She is the main character in an arrangement. Both partners appreciate their freedom and that unites them. The beautiful Marta too can do what she wants. Should she also have affairs, she is too smart to talk about it.

©Translation by Robert C.-E. Jenkins